Perhaps because we see them regularly, it's easy to take…

What We’re Working On: The Pacific Northwest Drought

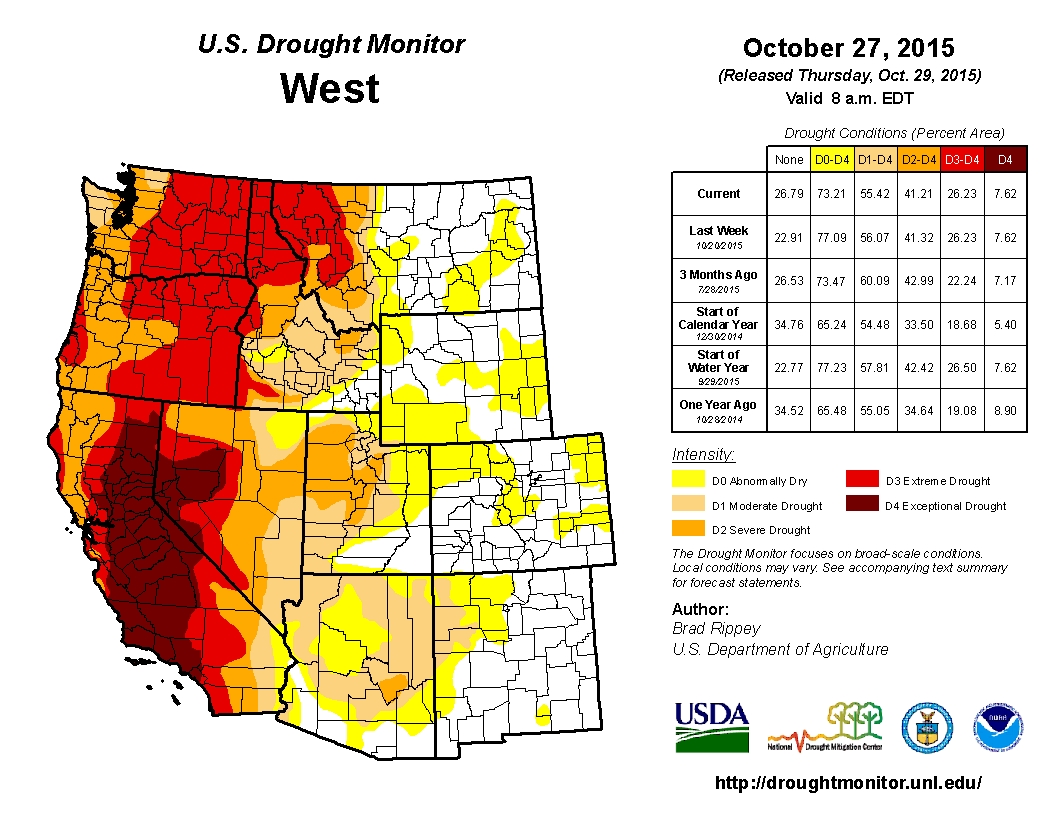

Is it climate change? Part of our normal cycle? A combination of both? Whatever the catalyst, we are in the thick of an extreme drought across British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. As of early November, the below-normal fall rains had brought little relief to the region. The USDA Drought Monitor still lists nearly all of Oregon and Washington’s drought status as either “Severe” or “Extreme”:

To make matters worse, the climate gurus at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center tell us it’s 95% certain we are headed for a “monster” El Nino for the fall and early winter of 2015 and 2016. That probably means warmer temperatures with less snow and rain, unless you live in southern California, in which case conditions are setting up for heavy rain and abnormally high snowfall in the mountains. Good for California—perhaps very good for California—but probably the last thing needed for Pacific Northwest water levels.

In late August, Vancouver’s Seymour River was running extremely low and warm. The river’s recovering run of pink salmon was holding at the mouth.

The same spot, two weeks later after seven inches of rain over a one-week period. A remarkable turnaround, with salmon moving upstream in the cooler, higher water. But the drought remained far from over.

Aside from the usual concerns about water for personal and business use, what do these conditions mean for the health of our waterways, fish and wildlife?

In September and October we completed a “boots-on-the-ground” research and photo excursion through central, eastern and southern Oregon where the drought has hit the hardest and where there has been no relief with the onset of fall. Here we found streams down to trickles with lakes and reservoirs at less than 20% capacity. Some lakes and important wetlands are completely dry. Many towns have enacted water restrictions and are looking for ways to conserve water and mitigate shortages in the future.

This story is under development, and we will add a number of in-depth reports from specific locations over the next few months. In the meantime, here’s a short photo essay and overview that gives you some perspective on the drought conditions in Oregon’s drier regions.

At Oregon’s Detroit Reservoir on the Santiam River, stumps and foundations from the original town site, flooded in 1952, lie exposed.

At Prineville Reservoir, now at just 30% of capacity, docks sit high and dry, well above the waterline.

Prineville Reservoir’s fishing platform sits, somewhat comically, far away from any fish.

Wickiup Reservoir, located in Deschutes County southwest of Bend, is at 14% capacity.

Treasure hunters sweep the Wickiup lakebed in search of valuables dropped overboard during years of more abundant water.

Davis Lake, one of Central Oregon’s most popular trout fishing destinations, holds a fraction of the water compared to its historic levels.

The salty water of Abert Lake, about 20 miles north of Lakeview in Lake County, normally covers an area 15 miles long (24 kilometers) by 7 miles (11 kilometers) wide and supports a vast population of brine shrimp. Today only a tiny patch of water remains at the lake’s lowest elevation. The brine shrimp have disappeared.

The water of Goose Lake, south of Lakeview and straddling the California border, is all but gone. Cattle graze on the vast lake bed which, when full, stretches for more than 25 miles (40 kilometers) north-south and nine miles (15 kilometers) east-west.

The Hart Lake water gauging station has nothing to measure but grass, rocks and cattle. Hart Lake, which normally covers over 7,000 acres (2,833 hectares), offers important waterfowl habitat when it contains water. Today, the dry lake provides little more than grazing land. The exposed lakebed contains ancient native artifacts and burial grounds, offering proof that comparable droughts have occurred in the past.

The Warner Wetlands, normally home to waterfowl and other birds, have been baked dry in the drought. When water is here, the wetlands support pelicans, Wilson’s phalaropes, sandhill cranes, white-faced ibis, Canada geese and many types of ducks and terns.

Ashland’s Emigrant Lake, which when full boasts an average depth of 53 feet and maximum depth of 160 feet, is now less than 10% full. The reservoir normally covers almost 880 acres (355 hectares) and provides boating and fishing for trout, crappies and bass.

Today the crew from the Ashland Rowing Club trains on the bit of water left in Emigrant Lake. On the plus side, there’s plenty of room to park cars and gear.